Author: Predrag Rajković

You have a product, service, any kind of offering to customers, and you are constantly wondering how can I make it better, how to attract more users, will they like the feature that is about to be released, will they use the product as I imagined, and will they use it at all… All these questions fall in the domain of product discovery, and they are all yelling – “Invest your time in product discovery!”.

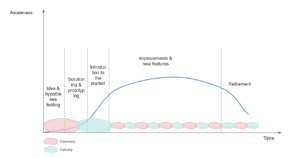

Let’s briefly set the stage. Looking at the product life cycle we can separate phases that the product goes through during its life. In general those phases could be – Idea, the initial phase where we explore problem to be solved and identify different opportunities that could lead us to achieving the goal that we have set in front of our product. Here we understand the problem which we are solving. First validation happens here, also. We are checking if our hypotheses around the problem are valid, i.e. does the problem exist for our future users and is it worth solving. Next phase would be creating potential solution, and testing through prototyping. After it, comes the phase of product creation (or development), testing and first release. Till now, our product is alive, it is getting traction, user base enlarges and we are considering new features that fuel growth of our product. Finally, as the time passes, our product enters the final phase of its life where we consider either its retirement and withdrawal from the market, or we pivot and try to give it a new life changing its focus, key selling points, problem it is solving, or target audience.

Product life cycle

Ok, so where is a product discovery here?

It happens in all those places where we increase our understanding of our product. It happens through different means – market research, user interviews, data analysis, feedback analysis, understanding of business goals… Therefore it might happen, and it happens in any part of the product life cycle, but we might say that it is the most intensive and crucial at the beginning of the product life.

Why crucial? Isn’t it crucial that we create and deliver a high-quality and technically superior product?

While it is important that the product we deliver is of a high quality, it is still essential that someone wishes to use it. In other words, creating the highest quality product, built using the latest achievements of technological progress, that no one wants to use is just a wasted effort. We have a spaceship, but no one wants to sail through space.

In other words, while delivery helps us build the product right (with the high quality and in an efficient way), discovery helps us build the right product (i.e. product that people want to use)…

And this is why product delivery is crucial – it is a set of activities helping us find out (discover) what our customers want and need, and helps us communicate those wishes throughout our company.

Before we jump into how we do discovery, let’s see who should be doing it. In general, you need the team to do the job well. The team should consist of people with different backgrounds. The more perspectives, the better as long as the communication can be held under control. As a rule of the thumb there should be 3-5 people as a core team engaged in discovery. Of course, it is possible and desirable to include additional subject matter experts when needed. Quite often there is a reference to 3 people accountable for the product overall and for the discovery also. They are called the 3 amigos, or the product trio. Those 3 people should come with the product management, design & UX, and engineering background.

That being said, let’s see what product discovery consists of. We might break discovery process into following activities:

1. Desk research

2. Empathizing with target user

3. Defining the opportunity space

4. Defining the desired outcome

5. Prioritizing opportunities

6. Solutioning and experimenting

7. Defining the MVP and MMP

8. The visual design

Please note that having said activities doesn’t mean that they are done linearly in successive order. Some of them are intertwined and happen iteratively.

Another thing to consider is time spent in the discovery process overall, and with it in each of these activities. There is a risk to spend too much time on a discovery. It might seem that we have never done enough analysys, that there’s always an angle or piece of information that we haven’t considered, or the stone that has not been turned. The best way to mitigate this risk, and not to reach paralysis by analysis state is to sandbox each activity. Yes, there’s a significant difference depending on the concrete product or a feature we are discovering. Some are obvious and we know a lot about them, while others are just a vague idea of what to create. But with some experience you will be able to estimate time for these activities. After all, if it turns out that you lack vital information to make a decision, you can dedicate more time to it.

1. Desk research

Typically, desk research encompasses reading different reports, studies, analysis, etc. The purpose of this phase is to collect initial information on the product you are considering, and its environment. Internet browsing is a useful way to get needed data, just be cautious of the source you are using. Currently a lot of people are using ChatGPT for this phase. Bear in mind that currently information on which ChatGPT 3 (which is available for free) is trained on, ends with 2021, which means that at the moment of writing this article (May 2023) information is already 2 years old.

Analyzing internally available data on product usage is a very important part of this research. Understanding the stickiness of our users, their behavior with our product, things they visit, where do they spend their time, what are they interested in, what do they buy, at which steps of process do they fall out, makes a cornerstone for further discovery.

During this phase we create the background picture, the scenery of our future product.

2. Empathizing with target user

If we haven’t done it before, here we have to define our target group of users, our customer segment, our user persona. We have to understand who we want to talk to, whose pains we aim to relieve.

Once we create the scenery and we know objective facts on our product and users it is time to get into the mind, into the subjective, emotional part of our users’ behavior. While in the first step, desk research we are talking mainly of quantitative methods, in this step we are predominantly using qualitative research.

In order to feel what customers feel and see our product with their eyes we include, one-to-one customer interviews, my preference goes to the unstructured interview as a format. Observation of users (or contextual observations) while they are using the product is another way. Ethnographic research could, also, be a technique of choice here.

As said, the purpose of this step is to understand our customers well, be as close to them, feel their pain. Only this will give us insight into what they need, and consequently what we should build.

3. Defining the opportunity space

In this part we investigate different opportunities laid in front of us. We are trying to identify problems customers have and formulate them in a form of the opportunity we, i.e. our product, might try to address.

Main source for opportunities is the previous step. There, we get under the skin of our customers and figure out what problems they feel. Now it’s time to reverse those problems in our opportunities and map them so that we have a visual representation. Though it might sound banal, this step is important as it is systematizing our knowledge of customers’ problems, helping us not forget some important opportunity, and, as we will see later, help us decide which opportunity we will put our effort into first.

Another important part of this phase is hypothesis testing. By listing different opportunities, we are actually embedding a lot of assumptions into our discovery. We might suppose users don’t visit our blog because they don’t find the content interesting, while the truth might be that they don’t even know our blog exists (i.e. our marketing is missing them), or vice versa. Assumptions have to be validated.

4. Defining the desired outcome

A product is a business category. This means its purpose is to bring some economic value to the company that is producing it. Therefore, none is created and led to serve itself. In order for the product management to be purposeful it has to lead the product toward fulfillment of certain goals. Therefore, we have to have clear outcomes that we want to achieve, both from the perspective of business overall, but also from the perspective of the product we are building. Put it differently, if we haven’t formulated where we want to go up to now, now is the last moment to do this.

Beware, here we formulate outcomes, meaning what we want to achieve, not outputs (which would be – what we want to build). For example, outcomes that we want to achieve as a business could be: increase our sales, or increase customer satisfaction, or increase the time our brand is in front of our customers’ eyes. Our product should serve these outcomes, or help in achieving them. Therefore, we formulate product outcomes so that they are inline with the business outcomes. Depending on our business, and role of the product in it, the outcome will be different. In other words, product outcomes will be different if we manage the single product in our company, obviously there will be a more direct relation to business outcomes, than if we manage one of the products in a company’s portfolio. Examples of product outcomes might be: increase time customers spent on our website, or increase sales via our mobile app.

I like how Teresa Torres puts it in a nutshell: “Business outcomes measure the health of the business. Product outcomes measure a change in customer behavior.”

5. Prioritizing opportunities

With outcomes defined, prioritizing becomes easier. Now we have our north star to which we are heading, and some opportunities become obvious to deprioritize. Let’s link it to the previous example. Let’s assume we are running a company website. Business goal is: Increase time potential customers are exposed to our brand. Linked with this, our product (website) goal might be: Increase time visitors spent on our website.

Also, let’s imagine we have identified following opportunities:

1. It is hard for visitors to find customer support page

2. Visitors spend little time on our pages because they are filled with text, and they don’t want to read it through

3. Visitors visit only one page because they don’t see anything interesting that they might continue reading

With our product outcome defined as above it becomes obvious that opportunity number 1 will not have a crucial impact on it. Or put it differently, the impact of opportunity 1 to our outcome would be lower than the impact of opportunities 2 and 3, meaning opportunity 1 is of a lower priority than the other two.

This doesn’t mean that we will never improve the ability of our users to find a support page. It just means that in this concrete case we have things to do that are more important for the company.

6. Solutioning and experimenting

Once we know where we will put our effort at this moment, it’s time to start working on solutions. Each opportunity can have several different solutions. Let’s assume that our top priority opportunity, i.e. opportunity for which we believe will have the biggest impact on the outcome, is opportunity number 3, visitors don’t see anything interesting to read. Here, we might have several solutions, for example: introduce a stripe with featured articles from our site, or introduce a widget showing the most read article, or create a recommended articles stripe, or make tips & tricks widget… In this step we should not only come to a solution, but also test it with end users. We don’t want to build something just based on our gut feeling. Gut feeling is ok, but should be validated in order to minimize the risk of building things that no one would use.

7. Defining the MVP and MMP

Now that we have the solution for the customer’s problem, we are considering the delivery phase, and we want to deliver the smallest meaningful set of features to our users as soon as possible. In other words, we want to define the MMP (Minimal Marketable Product) which is a very important concept. Widely used term is MVP (Minimal Viable Product), however, this term has different descriptions ranging from a literally minimal piece of code that shows that something works and that can help us prove that we can deliver something, to a product that is capable of being accepted on the market. Definition with this wide range of understanding inevitably introduces misunderstanding between product stakeholders.

In order to avoid confusion, I believe it is beneficial to separate things. Minimal Marketable Product is a set of features without which launching of the product would be meaningless. Imagine you are working on a new app for video entertainment. Here, the bar has already been set high by players like Youtube, Disney, Netflix… So launching an app with the mere possibility to play and pause video wouldn’t make any sense on the market. At the same time, there is a need for people working on a product to receive feedback as soon, and as often as possible. Here the MVP jumps into a play. Through MVP, the product manager and the team can decide what is minimal that could be shown to important people to receive feedback.

Defining MMP will be significantly impacted by the estimates of complexity of our product. This assumes that we have to have some, at least, high-level estimates on how much our products will “cost”. With this in mind we will be able to fine tune the MMP, to include only what is really necessary in the first release, while other features will be planned for later releases.

8. The visual design

All previously described steps bear tons of dilemmas and confronted opinions on how they should be done and what they should include, but this step has a controversy highly embedded in itself. There are significant differences between product people in approach to when the visual design of the product should be delivered. You might push it as close as possible to the ideation phase, but there are also reasons to push it as much as possible to the later phases of the product discovery.

I would say that this depends, among other things, on how you have organized teams and work processes in your organization. If you don’t have a product trio as a body to drive the product through the discovery (and also through delivery), then it makes sense to postpone development of final visual design (pixel perfect) to later stages. On the other hand, if a designer is incorporated through the whole discovery process, you will have some design drafts from early beginnings.

My view on this is that at the end of discovery, you have to have at least high-level design, on the level of wireframes. The reason for this is that you can discuss the future product with the development team in more detail. Developers don’t need pixel perfect design to understand what should be built, or to give some assumptions on the complexity of the task that should be done. For these purposes, wireframes will do just fine. Yes, it would be better if we would have the final design, so that we know all the details on user interactions, but if this means that, due to organizational or personal reasons, we have to wait too long for the design, then the lost time is not worth this piece of information.

With this we conclude the discovery phase. In a nutshell, the deliverable of product discovery should be clear understanding of what we want to do, described in just enough details that engineers can start wrapping their heads around concrete execution problems, i.e. going into technical details and start providing answers to the “How will we do it?” question.

9. Next steps

So, what comes next? Once the discovery part is finished we are entering the delivery phase. This means that we have to prepare for the development. In order to do that we need to communicate the discovery results (or, the what we are building) to the rest of the organization. Good way to do this, and to include a wider audience, is organizing so-called User Story Writing Workshops. After which we should be engaged in some sort of delivery planning, be it release planning event, or some other, less formal event, after which we are entering in the delivery phase.

As said before, once in delivery it doesn’t mean that we forget about discovery. Firstly, through delivery we constantly receive feedback on what we are building. This comes from the team, system architect, designers, other product people, but also from stakeholders during demos of our work in progress.

Secondly, while in delivery for one feature, we are working on discovery of new features that will come to be delivered in a week, month or a quartal.

One thought on “Product discovery, what, why, how & who?”

Comments are closed.